MENU

CZ | CZK

CZ | CZK

No results found

Search Suggestions

The Best of Both Worlds

Explore Life Science

- Off the Bench

- Bright Minds

Ann Kennedy unites the fields of biology and mathematics like no one else. With the help of computer modeling, she describes real-life processes. And this is how the neuroscientist has recently discovered how mice regulate aggression.

Ann Kennedy is among the few theoretical neuroscientists who are capable of translating their mathematical work into real experiments”, says Larry Abbott, “this is a gift!” Abbott was her PhD supervisor at Columbia University – and he is not the only contemporary who is full of praise. The online portal “Spectrum” of the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative has published an extensive article featuring the researcher who is currently working as an assistant Professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. The magazine describes her as a “rising star” in the academic firmament. It describes her as bridging a gap between biologists and computer scientists, and it mentions that she is great at finding just the right mathematical approach for every problem.

Ann Kennedy is soft-spoken. During the interview, she comes across as almost shy. Almost as if it would be easier for her to let others speak about her and her successes – even though she is an eloquent storyteller, which may seem unusual for someone who is so deeply immersed in the world of numbers, data and codes.

In fact, she has always pursued a multipronged approach, as she was interested in biological processes in the brain as well as in mathematical modeling. She uses the following analogy to describe her motivation: “You can look at a cup on your desk and see a cup. But one could also consider the intricacies of how a software must be designed so that it will be able to recognize the cup.” It’s the latter approach that sums up her passion.

Ann Kennedy is soft-spoken. During the interview, she comes across as almost shy. Almost as if it would be easier for her to let others speak about her and her successes – even though she is an eloquent storyteller, which may seem unusual for someone who is so deeply immersed in the world of numbers, data and codes.

In fact, she has always pursued a multipronged approach, as she was interested in biological processes in the brain as well as in mathematical modeling. She uses the following analogy to describe her motivation: “You can look at a cup on your desk and see a cup. But one could also consider the intricacies of how a software must be designed so that it will be able to recognize the cup.” It’s the latter approach that sums up her passion.

Read more

Read less

Successful breakthrough

As a result, Ann Kennedy’s major accomplishment is the fact that she can literally look behind the cup – by developing tools that help us understand how the brain works. This unique skill has also earned her the “Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology 2022”, worth USD 25,000.

Kennedy’s research provides new knowledge on how the mouse brain regulates social behaviors – for example, aggression. The results, she says, are a “culmination of many other works”. Are they a breakthrough? “I think so”, she says with a cautious smile. “Because this one specific brain region can be stimulated to trigger an attack in a mouse, biologists used to think that in this area, a specific subgroup of neurons existed that would make the decision to attack – similar to flipping a switch.” In contrast, her work now shows that this brain region acts more like an indicator for the aggressive motivation of the animal, and that it exists independently from the situation, whether a fight occurs or not.

“We saw activation in a large number of neurons which were active over a prolonged period of time.” Phrased in lay terms: archetypal behaviors of animals, which include aggression, are not simply up- and downregulated in the brain region of the hypothalamus using an all-or-nothing switch. The motivational drive for these behaviors is finely tuned via a “population of neurons” – similar to a volume dial, the intensity of which is increased or decreased slowly.

In order to understand what goes on between sensory input and motor actions in the brain, Kennedy and her team used micro-endoscopes which they fastened to the heads of the mice. While mice were free to run around, the team of researchers observed which types of neurons were active. “The results helped us understand how the brain maintains states of motivation”, says Kennedy. When, for example, the mouse sees a predator – in this study, a rat – or enters an altercation with another mouse, it will not forget these events right away. “Increased excitation remains, and it changes the animal’s behavior.” The neuron population discovered by her team thus correlates with the sustained willingness of the animal to fight – and not with the fight itself.

As a result, Ann Kennedy’s major accomplishment is the fact that she can literally look behind the cup – by developing tools that help us understand how the brain works. This unique skill has also earned her the “Eppendorf & Science Prize for Neurobiology 2022”, worth USD 25,000.

Kennedy’s research provides new knowledge on how the mouse brain regulates social behaviors – for example, aggression. The results, she says, are a “culmination of many other works”. Are they a breakthrough? “I think so”, she says with a cautious smile. “Because this one specific brain region can be stimulated to trigger an attack in a mouse, biologists used to think that in this area, a specific subgroup of neurons existed that would make the decision to attack – similar to flipping a switch.” In contrast, her work now shows that this brain region acts more like an indicator for the aggressive motivation of the animal, and that it exists independently from the situation, whether a fight occurs or not.

“We saw activation in a large number of neurons which were active over a prolonged period of time.” Phrased in lay terms: archetypal behaviors of animals, which include aggression, are not simply up- and downregulated in the brain region of the hypothalamus using an all-or-nothing switch. The motivational drive for these behaviors is finely tuned via a “population of neurons” – similar to a volume dial, the intensity of which is increased or decreased slowly.

In order to understand what goes on between sensory input and motor actions in the brain, Kennedy and her team used micro-endoscopes which they fastened to the heads of the mice. While mice were free to run around, the team of researchers observed which types of neurons were active. “The results helped us understand how the brain maintains states of motivation”, says Kennedy. When, for example, the mouse sees a predator – in this study, a rat – or enters an altercation with another mouse, it will not forget these events right away. “Increased excitation remains, and it changes the animal’s behavior.” The neuron population discovered by her team thus correlates with the sustained willingness of the animal to fight – and not with the fight itself.

Read more

Read less

A born explorer

Ann Kennedy grew up in a suburb in northern Virginia. Both parents worked as engineers in the computer industry – her mother developed operating systems for the first ATM machines – and they taught Ann and her brother programming when they were only in elementary school. But she also played soccer, was active in the Girl Scouts and took piano lessons. Her grandfather, also an engineer, was another formative influence in her life, and it was in his workshop that she was often found tinkering.

Even when she was small, she always wanted to get to the bottom of things and understand how things work. She took every opportunity to learn something new. While still in school, Kennedy did a practicum in a stem cell laboratory at Children’s National Hospital, and she went on to study biology and biomedical technology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. She took as many courses as possible in subjects that were new territory for her: signal processing, information theory, linear algebra. In this way, she built a broadly designed toolbox which would prove to be helpful in her later research.

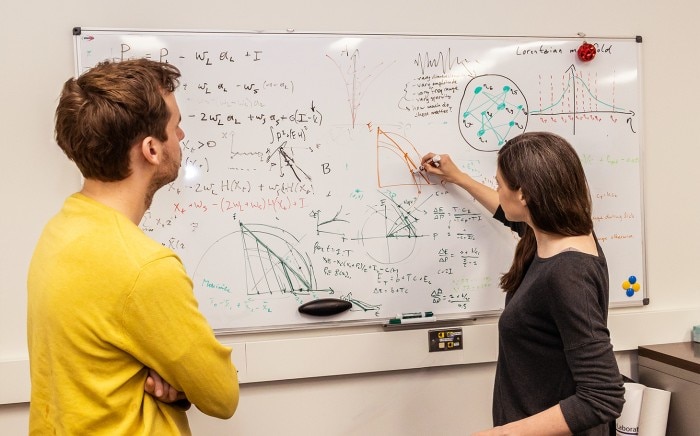

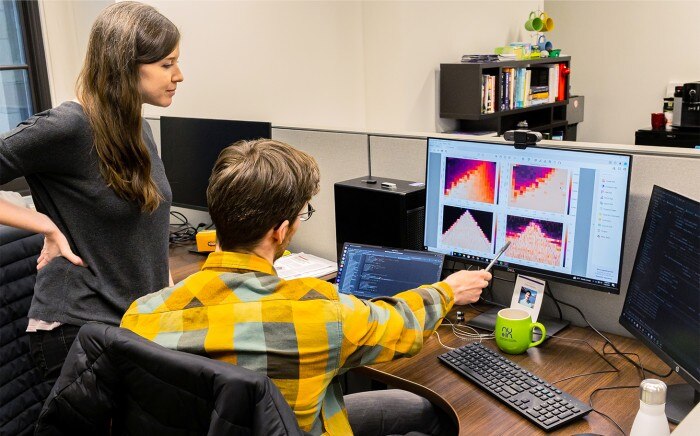

How would she describe herself as a person? “That’s a strange question”, she says and pauses for a few seconds. “Recently, I have invested so much time in building my own lab that my thoughts generally revolve around my work”, she answers. Her laboratory, which she started in 2020, is located on the 5th floor in a building in downtown Chicago. “Some people are surprised when I take them here. All you can see are people sitting at desks”, she tells us. “We spend most of our time looking at monitors; we program, we write publications and we discuss our work.” Data, codes and diagrams are her world. From time to time she also teaches postdocs and students, which she considers a welcome change.

Ann Kennedy grew up in a suburb in northern Virginia. Both parents worked as engineers in the computer industry – her mother developed operating systems for the first ATM machines – and they taught Ann and her brother programming when they were only in elementary school. But she also played soccer, was active in the Girl Scouts and took piano lessons. Her grandfather, also an engineer, was another formative influence in her life, and it was in his workshop that she was often found tinkering.

Even when she was small, she always wanted to get to the bottom of things and understand how things work. She took every opportunity to learn something new. While still in school, Kennedy did a practicum in a stem cell laboratory at Children’s National Hospital, and she went on to study biology and biomedical technology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. She took as many courses as possible in subjects that were new territory for her: signal processing, information theory, linear algebra. In this way, she built a broadly designed toolbox which would prove to be helpful in her later research.

How would she describe herself as a person? “That’s a strange question”, she says and pauses for a few seconds. “Recently, I have invested so much time in building my own lab that my thoughts generally revolve around my work”, she answers. Her laboratory, which she started in 2020, is located on the 5th floor in a building in downtown Chicago. “Some people are surprised when I take them here. All you can see are people sitting at desks”, she tells us. “We spend most of our time looking at monitors; we program, we write publications and we discuss our work.” Data, codes and diagrams are her world. From time to time she also teaches postdocs and students, which she considers a welcome change.

Read more

Read less

Crazy about science

She would not mind traveling more. Sometimes, she manages to tack on a few extra days to a conference, for example, following a workshop in Puerto Rico. In California, where she worked as a postdoc, she learned to appreciate hiking. “Here, in Illinois, mountains are not so much part of the scenery”, she says, but still, she tries to get out into nature as much as possible to go for long walks with her husband. And yes, when time allows, she loves to cook to relax, and beyond that, she is a book fanatic, reading fictional novels as well as nonfiction. “What I love most is to immerse myself in the world of ideas of scientists. I love discovering books about scientific theories from past decades and find out how our thinking in the different disciplines has changed”, reveals Ann. After all, science is her dream job.

She would not mind traveling more. Sometimes, she manages to tack on a few extra days to a conference, for example, following a workshop in Puerto Rico. In California, where she worked as a postdoc, she learned to appreciate hiking. “Here, in Illinois, mountains are not so much part of the scenery”, she says, but still, she tries to get out into nature as much as possible to go for long walks with her husband. And yes, when time allows, she loves to cook to relax, and beyond that, she is a book fanatic, reading fictional novels as well as nonfiction. “What I love most is to immerse myself in the world of ideas of scientists. I love discovering books about scientific theories from past decades and find out how our thinking in the different disciplines has changed”, reveals Ann. After all, science is her dream job.

Read more

Read less

Related documents

Read more

Read less

Learn More?

Cick here to the website:

Read more

Read less